Abbot Nicholas, on Holy Resurrection Monastery’s Practical Ecumenism blog, continues his thoughts on Pope Benedict’s “Reform of the Reform” here and here. We discussed the first part of Abbot Nicholas’s thoughts here.

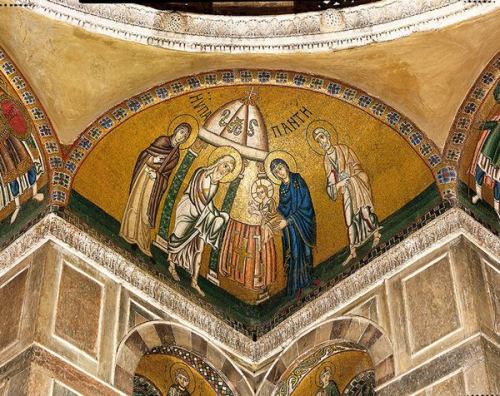

(Pictured above: The dome of St Isaac’s Cathedral, Petrograd)

————–

I’m continuing my reflection on Cardinal Ratzinger’s (as he then was) 2000 book, The Spirit of the Liturgy.

In The Spirit of the Liturgy Cardinal Ratzinger is not only speaking of ‘image’ in the narrow sense of an icon. He is including in this understanding all Christian sacred symbolism, all liturgical action, including space and time and also sacred music. Celebration of the eucharistic prayer ad orientem or ad populumwould be included in this discussion of the image or the symbolic. Ratzinger says that we need sacred space and sacred time, mediating symbols so that precisely through the image, through the sign, we learn to see the openness of heaven. Surely, it is to heaven, to the Father that the eucharistic prayer is addressed. This symbolism has a long history in all the Apostolic Churches. It is always the Risen Christ, even His image on the Cross to whom the community looks as the true Oriens.

Cardinal Ratzinger asks: “Is this theology of the icon, as developed in the East, true? Is it valid for us (in the West)? Or is it just a peculiarity of the Christian East?” (p. 124.)

He goes on to say that the West in the first millennium emphasized, almost exclusively, the pedagogical function of the image. This is born out in such great Western Church Fathers as St. Augustine and St. Gregory the Great. The so-called Libri Carolini, as well as the synods of Frankfurt (794) and Paris (824), came out against the poorly understood Seventh Ecumenical Council. This was partly due to faulty translations of the Greek text of the Council’s decrees into Latin. But the problem went deeper, touching on the theological function of symbols which in turn speaks to their anthropological function. In the East, the defeat of iconoclasm was the triumph of a vision of human life materially linked with the Divine through the Incarnation. Ratzinger certainly does not claim that the West rejected this vision—indeed it did not. It was not rejected, because it was not fully understood.

One suspects that the full consequences of this disconnect did not emerge for centuries, as long as it was submerged beneath the obvious similarities between the art of Christians on both sides of the Latin/Greek divide. At least until the thirteenth century the fundamental orientations of iconography remained essentially the same in East and West. But the Renaissance did something quite new. “Sacred art” now became merely “religious art.”

Now we see the development of the aesthetic in the modern sense, the vision of a beauty that no longer points beyond itself but is content in the end with itself, the beauty of the appearing thing. (p. 129).

Ratzinger sees Baroque art, in its Christian form, as an attempt to recapture the sacred. However, it is here that we see most clearly the ancient tendency of the West to regard art and symbols as pedagogical tools.

In line with the tradition of the West the Council [of Trent] again emphasized the didactic and pedagogical character of art, but as a fresh start toward interior renewal, it led once more to a new kind of seeing that comes from and returns within. (Ibid.)

In short, what was missing from the western Baroque was precisely its iconic, which is to say liturgical function. Religious art did not seek to effect union between humanity and divinity, but merely to encourage, or describe, the inner experience of a highly individualized spirituality. Baroque art was capable of an intense emotionality (Ratzinger speaks of it as an “alleluia in visual form”, p. 130), but it was not itself a sacrament making possible the participation of human emotion—indeed, any aspect of human experience—in divine reality. We have here the old problem that the West, especially after Augustine, could never quite overcome: how can material creatures participate in immaterial life? The Baroque is, in many ways, the traditional Western solution expressed in a new way: we participate in God’s life through an inward adjustment of our emotional and intellectual capacities. We feel, we think like God, but we cannot be gods. And this means the world we inhabit, however beautifully it might reflect, by analogy, divine power, cannot be drawn up with us into divinized life.

Here, I have to inject my own observation that this problem that I have called “Western” penetrated deeply into the Greek, Arabic, Slavic and Balkan churches of this same period. The adoption by Orthodox Churches of Baroque styles of visual and musical art is well known. However, it would not be true to say that the more ancient, patristic view of the image as sacrament was entirely lost. The forms changed, and to some extent this inevitably obscured the theology of image, but not entirely. Icons retained their specifically liturgical function. Instrumental music was never accepted in the East. However powerful the enticements of Counter-Reformation Catholic vitality, the Orthodox retained an instinctive sense that art was more than a way of seeing within, but rather pointed outwards, beyond itself to the divine heart of reality itself.

By the time of the Enlightenment an impoverished view of the image deprived the Church of a stronger defense against the secularization of cultural and intellectual life. This in turn was the foundation for a fully developed “iconoclasm.”

The Enlightenment pushed faith into a kind of intellectual and even social ghetto. Contemporary culture turned away from the faith and trod another path, so that faith took flight in historicism, the copying of the past, or else attempt at compromise or lost itself in resignation or cultural abstinence. The last of these led to a new iconoclasm, which has frequently been regarded as virtually mandated by the Second Vatican Council. (p. 130.)

In the end the “new iconoclasm” of which Ratzinger speaks is not simply the abandonment of images, although it may at times involve this. Sometimes the kind of iconoclasm to which he refers could even take place within an explosion of images in a quantitative sense (as may be seen in many places in the 19th century, for example, with the embrace of kitsch). What matters is not so much the number of images and other symbols, nor even their form, but rather the theological and anthropological vision that determines how they are seen and experienced, either solely as expressions of individual spirituality or as means of communion. Cardinal Ratzinger says:

The Church in the West does not need to disown the specific path she has followed since about the thirteenth century. But she must achieve a real reception of the Seventh Ecumenical Council, Nicaea II, which affirmed the fundamental importance and theological status of the image in the Church. The Western Church does not need to subject herself to all the individual norms concerning images that were developed at the councils and synods of the east, coming to some kind of conclusion in 1551 at the council of Moscow. Nevertheless, she should regard the fundamental lines of this theology of the image in the Church as normative for her. (pp. 133-4.)

In any discussion involving the broad generalizations of “West” and “East” there is often the danger of making out distinctions in expression to amount to differences in faith. In ecumenical, or anti-ecumenical, polemics this danger is often eagerly embraced. I would hate to think that my reflections, and still less Ratzinger’s thought on which they are based, should seem to fall into the category of polemic.

The basic faith of the universal Church is, and has always been, that Jesus Christ unites in Himself all things in heaven and on earth (cf Ephesians 1:10). This is a fact, the fact of the Incarnation, and it forms the irreducible content of Christian hope. There are certain consequences of this faith in terms of the way in which Christians have access to the Incarnation as a historical and trans-historical fact: notably the sacraments, of which the Church herself is the first. This basic theological truth, and the practice it enlivens, form the common patrimony of the Eastern and Western Churches. It unites at the deepest level.

What divides, or at least distinguishes East and West, then, is not so much a matter of faith or practice, but of ways of explaining this faith and practice. What really divides us, then, is theological language.

I think that this is at least what Ratzinger thinks (and I certainly agree with him). What he is seeking to do in The Spirit of the Liturgy is not to make Roman Catholics adopt oriental icons or liturgical forms. Not at all! What he is trying to do is point out something that Roman Catholics already know is missing from their theological language, including their non-verbal, their iconic, language. The fact that they can sense that it is missing is a sign that they belong to the ancient Church, not that they are excluded from it. What Ratzinger sees in the Seventh Ecumenical Council is a way of giving back to Catholics something they have always known, but have never been able to completely express within the parameters and limitations of their own theological discourse. He seeks to give them a language to help explain what they have always tried to see within the “way of seeing” that is sometimes revealed, sometimes obscured, in the symbolic arrangement of their worship and devotional lives.

In short, it is not only Eastern Christians who are convinced that, in Christ, heaven and earth are mingled together (as one of the hymn writers of the Byzantine tradition puts it). Western Catholics believe this also. They know it; it informs their attitude to the world, to nature, to care for the poor, to the construction of Christian community, to the role of natural law and in so many other different aspects of the genius of the Roman Catholic tradition. What Ratzinger wants to do is strengthen this tradition by introducing, or re-introducing to it, a way of seeing that it will recognize with joy, because it already corresponds to its deepest insights and longings.

This is ecumenical work at the highest level. I am deeply grateful for it.